Radical Disestablishment

Nathan S. Chapman & Michael W. McConnell, Agreeing to Disagree: How the Establishment Clause Protects Religious Diversity and Freedom of Conscience. Oxford University Press, 2023. 226pp.

The Establishment Clause and its incorporation haven’t gone far enough. All things need to be disestablished. A principle of non-establishment should pervade our politics. The government should not mold the beliefs, opinions, and pieties of its people. That’s the message of Nathan Chapman and Michael McConnell’s book on the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, Agreeing to Disagree. Though the Clause in question is “solely about religion,” it can, the authors argue, be repurposed to “protect cultural pluralism.” Secretly imbedded in the Establishment Clause is not just a jurisdictional provision. That is, not just what the framers of the First Amendment intended the Clause to do. Rather, there is a political principle of non-establishment that has been worked out over time but has still yet to reach its full potential. The framers of both the First and Fourteenth Amendments built so much better than they knew.

Defining Establishment

The authors agree that any interpretation of the Establishment Clause must be rooted in history and historical understanding, namely, that of the founding fathers. The problem, they say, is that the Courts have used faulty or incomplete history. A more thorough investigation is warranted. As we will see, however, this new investigation arrives at all the same basic conclusions of standing Establishment Clause jurisprudence. For Chapman and McConnell, perhaps the biggest problem is that “historic principles of disestablishment” have not be thoroughly applied to our own day. What is needed is radical disestablishment, true neutrality. This, they believe, is the real historic principle brought to life. And their historic analysis betrays a search for perennial principle rather than historic practice and historic assumptions, and historic limits.

It is the book’s use and abuse of history, therefore, that we will focus on most. More revealing, however, is that the book’s conclusions are not bound or informed by history, but rather betray other animating, supposedly timeless principles of political morality inserted into the Establishment Clause for ulterior ends. The book has an agenda, it is polemical.

Chapman and McConnell are right to call out the “truncated history” of the Supreme Court’s treatment of the Establishment Clause. Early on, it relied solely on “one event in one state: the rejection of Patrick henry’s Assessment Bill in Virginia in 1785 in favor of Thomas Jefferson’s alternative Bill for the Establishment of Religious Freedom.” (Despite their protest, the authors cite Madison and Jefferson more than any other founding-era figures.)

This episode was read back into the First Amendment as an expression of its objective and intent, namely, separation of church and state. Chapman and McConnell, again, rightly see this notion as “overly simplistic” and “far more hostile to religion, than anyone in the founding generation could have imagined.” Indeed, as I’ve shown before, this erroneous reading of the First Amendment was not even Thomas Jefferson’s. Further, it was not even the idea presented in the (in)famous letter from which it was taken.

Yet, already here, Chapman and McConnell begin to show their hand, their own truncated history. The Establishment Clause did, indeed, present a principle, they say, just not Justice Brennan’s or Justice’ Black’s. “The true evil of religious establishment contemplated at the adoption of the First Amendment was the use of government power to foster or compel uniformity of religious thought and practice.”

The authors, of course, acknowledge that, at first, this protection against uniformity was only applicable to the federal legislature, and that, by contrast, various forms of establishment prevailed in the states. Indeed, based on the definition of establishment given in Agreeing to Disagree, every single state had aspects of establishment.

That said, the reader can already predict where this is going. A general principle is going to be extracted from particular practice; the provisions and compromises of the late eighteenth century are about to be expanded into ready-made, expansive principles for the present.

Even in the historical story told by Chapman and McConnell, the Americans are cast as breaking from an “establishmentarian tradition” of England that did not protect “free exercise” of religion. The focus of Agreeing to Disagree is not the Free Exercise clause, but we should note here that McConnell has devoted some attention to the topic elsewhere and, moreover, that it is not at all clear exactly what the term, “free exercise,” meant in the late eighteenth century. McConnell criticizes Jefferson, in fact, for being too archaic in his understanding of the concept and constitutional provision.

Along the way, in the historical section of Agreeing to Disagree, we see the same assumptions as those allegedly being chastised for truncated history. For instance, mentioning the Test and Corporation Acts of late seventeenth century England, Chapman and McConnell suggest that the main accomplishment of the acts was to “foster hypocrisy” because it “made no attempt to determine a person’s genuine beliefs.” Hence, Jefferson was right to say that established religion “begets habits of hypocrisy.” So, such laws are necessarily invalid either because they cannot peer into the souls of men, or because laws should not attempt to do such a thing. Both are correct, of course. Laws cannot do either. Chapman and McConnell are using a double standard. Laws that try to police internal belief are bad, but laws that merely regulate outward profession and practice and also bad. The conclusion of the book is already given away: regulation of religion is per se wrong. Promotion of pluralism is good. Diversity is our strength.

We must back up. What is an establishment according to Chapman and McConnell? Their definition is not a bad one. There are six elements of establishments: 1) control over doctrine, governance, and personnel of the church; 2) compulsory church attendance; 3) financial support; 4) prohibitions on worship in dissenting churches; 5) use of church institutions for public functions; and 6) restriction of political participation to members of the established church.

Now we come to the theories of establishment—there are two—which Chapman and McConnell curiously consider to be “two different, almost antithetical rationales.” One is theological, the other political. The first is “aimed to glorify God” and to “shape public opinion.” The second is predicated on the “utility of religion” to political life. Again, the authors call these supposedly dueling rationales “logically antithetical” but notice that they were often employed in tandem. With no further demonstration of this antithesis provided, it is not at all clear how the two rationales conflict. That the establishment of religion is to the glory of God and protection of the Christian religion does not negate that it is also useful to the state for producing ideal citizens or shaping public opinion. Indeed, the second rationale only works if the first is believed.

More to the point, the definition above, while not wrong in theory, suffers from problems in the context to which it was applied. Point six (6), for instance, references the restriction of political participation to members of an established church. What of the generally Christian tests for office found in the states that, nevertheless, reference no particular denomination? What of the provisions in New Jersey wherein only Protestants could hold public office? No single established church is in play, yet there are religious restrictions on civil life. Trinitarian Protestantism does not constitute an established church, but it does, loosely, constitute an established religion, of the American variety. Such requirements are now outlawed for that reason.

Point one (1) features similar quirks. Historians would search in vain for a time when the Massachusetts governor or General Court dictated doctrine to the church. No Protestant would have assumed they could. Issuing calls for synods, wherein ministers would determine dogma, or limiting the franchise to those under care of incorporated churches, or exiling notorious heretics, was not control of doctrine. There was no state in the late eighteenth century that was controlling the doctrine of an established church, unless what Chapman and McConnell mean limiting the scope of acceptable doctrine preached. In which case, the other elements of the definition account for it.

Defining the Clause

In any case, what matters more than the definition of establishment at this stage is why the Establishment Clause was adopted. It’s important to get this right because “The proper interpretation of the Establishment Clause tells us much about the character of the American republic and our political culture.” We will find that for all their emphasis on robust history, the meaning of the Establishment Clause for Chapman and McConnell is not tied to or limited by the original public meaning or original intent and purpose. This will become clearer through their affirmation of incorporation. Chapman and McConnell are thoroughly Madisonian. They admit that he lost the debate on the First Amendment in 1789 but “arguably won it after the Civil War, when federal constitutional protections for individual freedoms including religion were applied to the states.” Often hailing Madison as the true architect of the Bill of Rights, this conclusion permits the authors to maintain a progressive originalism. The final, true form of the constitution is discovered or actualized only after incorporation because it was then that Madison’s desires, inaugurated in 1789, were consummated.

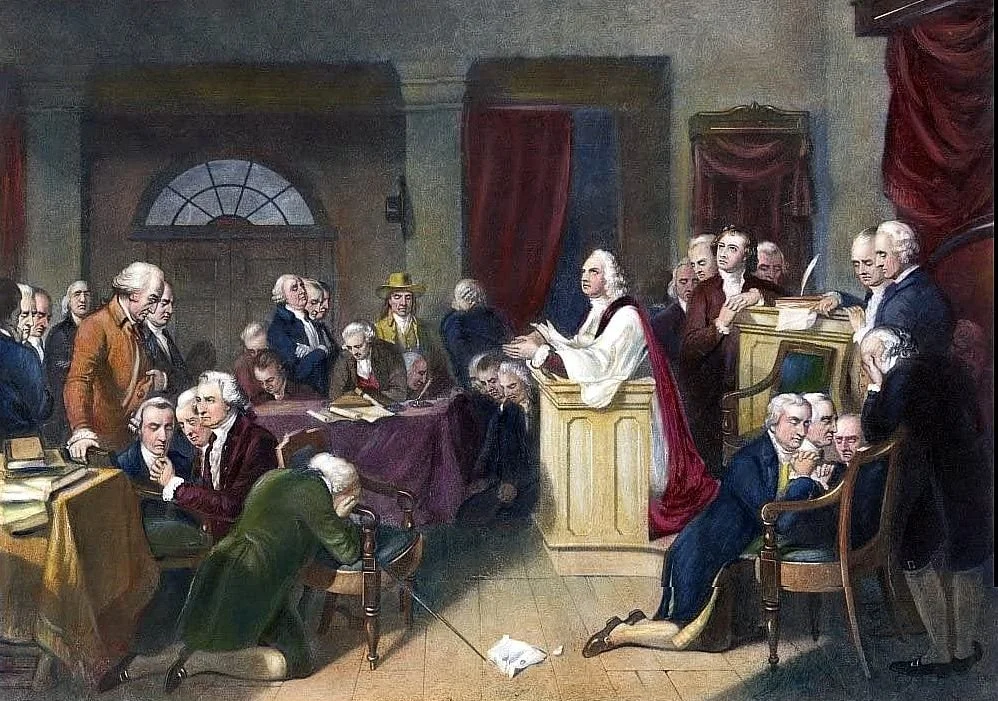

The scant debates over religion at the Constitutional Convention recounted briefly by Chapman and McConnell do shed light on the original meaning of the religion clauses. Philip Munoz has covered this material more fully. Whereas Madison wanted preemptive incorporation inserted into Article I, the rest of the First Congress rejected it. So too were provisions explicitly protecting individual right of conscience cut out. Examining the proposals of Elbridge Gerry, Samuel Huntington, Samuel Livermore, and Fisher Ames in light of the final product, it becomes evident that what was intended by the First Amendment was to 1) prevent a federal establishment and 2) protect state establishments. Indeed, this was Thomas Jefferson’s understanding of the amendment. New Englanders like Huntington wanted to ensure that no state claim could arise in federal court against state religious taxes and the like. Livermore likewise sought to remove “the entire subject of religion” from federal legislative jurisdiction. The Establishment and Free Exercise provisions were indeed federalist provisions. Incorporation was not assumed nor desired by any save Madison. That the final product was a consensus document precludes Madison’s musings from controlling meaning and purpose. No individual right was intended in the religious clauses. How could it? The federal government was entirely incapable of enforcing or protecting one in this regard.

The reasoning Chapman and McConnell on how incorporation is then possible in the late nineteenth century is telling. “We believe the Court’s conclusion that the Establishment Clause now applies to the states is mostly correct, but that the Court’s reasoning has been faulty.” In other words, the destination is correct, the textual vehicle is the only problem. Chapman and McConnell think privileges and immunities a better vehicle than due process, a technical objection that, again, changes nothing about the result. The authors are convinced that the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment intended Section One to apply to all individual freedoms in the Bill of Rights. Meaning, all such rights, all privileges and immunities of American citizens, were to be incorporated, that is, enforced against the states. All rights deemed “fundamental” or “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.”

Chapman and McConnell recognize a problem, however, when it comes to the Establishment Clause. It was never understood as protecting an individual right, as we have said. Its only object was the protection of state establishments, the state prerogative to regulate the morals of citizens. As both Justices Potter Stewart and Clarence Thomas have recognized, the incorporation of the Establishment Clause since 1947 has flipped to the Clause on its head, weaponizing it against exactly what it was meant to protect. But Chapman and McConnell possess a ready-made solution. As it turns out, they claim, the Establishment Clause is not merely a jurisdictional provision. It has a secret, “dual nature.” The Clause protects states from encroachment, but it also prevents Congress from establishing a national religion. The first part cannot be incorporated but the second, apparently, can. The first part was nullified when states voluntarily disestablished. The second part is “easily understood as a personal rights provision.”

Nevermind that no one understood it this way at the time of ratification. Even Madison and Jefferson, though they may have desired otherwise, understood that the Establishment Clause had not provided an individual right. Nevermind the stated original purpose of the provision. Nevermind that the first word of the Amendment is “Congress.” Nevermind that the Amendment was preventative, one of negation. Congress cannot do x y z. How, at the time of the Fourteenth Amendment, would the provisions of the Establishment Clause have been understood as constituting a personal privilege or immunity of American citizens? Was the concern at the time that state-level religious establishments were persecuting freed slaves? No one said so.

But somehow, secretly imbedded therein is a personal right to be free from regulation of religion, a non-establishment principle “easily” and “logically” capable of incorporation. Chapman and McConnell say little more. This is the extent of their reasoning which is truly bizarre and specious. Any semblance of historical fidelity dissipates at this stage of the case made in Agreeing to Disagree. What has taken its place is the own preferred political morality of Chapman and McConnell even as they continue to insist that “the historically informed purposes of the Establishment Clause give guidance” to their encounter with contemporary jurisprudence.

The confused and ahistorical analysis of Chapman and McConnell is most evident in their treatment of bible reading and prayer cases.

Defining Coercion

A revealing part of the book, illustrative of the position of the authors, comes in the section on school prayer and bible readings. Any religious exercises in public schools are (directly or indirectly) coercive, the authors agree with Engel and Schempp, because even if students are permitted to opt-out or excuse themselves, such exercises facilitate social pressure. Meaning, in an environment that explicitly prefers Christian practice, Jews and Muslims might feel uncomfortable and conform out of social anxiety.

Indoctrination in the principles of neutrality and pluralism, that religious exercises are coercive, that, however, is somehow not coercive. Things like neutrality and pluralism could never be coercive, of course.

The principle of the Establishment Clause, we are told, is that the government should not create uniformity of values, opinion, or belief. “When government is used to mold the minds of the people in conformity to political strength, the odor of establishment is in the air.” Hence, “A broader spirit of disestablishment is needed to block such attempts [of establishment] as they relate to other ideologies.”

When the Court in Engel and Schempp removed prayer and Bible reading from classrooms, this was “the Court’s finest hour with the Establishment Clause.” Why? Because it illustrated “how the principles of historic disestablishment can be applied, convincingly, to modern circumstances.”

Earlier, the authors had said that these things need to be left to the people with governmental thumb on the scale. “What is certain, though, is that the Establishment Clause, if properly understood and enforced, would help to ensure that the people decide that answer [of the future of American religiosity] for themselves, through personal and collective persuasion and not in legislatures or courts.”

Now, despite these practices being widely practiced, the Court did the right thing in “the face of public opposition and long-standing practice.” It turns out, the government can put its thumb on the scale so long as it is toward the principles of the Establishment Clause—neutrality and pluralism. Ideologies can behave like religions, just not the ideologies of neutrality and pluralism and freedom and the rest. Non-coercion. That’s the principle.

Not to worry, Christian prayer in public schools is not a founding-era tradition because, the authors tell us, there were no public schools until the 1830s. Therefore, the late eighteenth century expectations for schooling are inapplicable. Moreover, the “common school” movement of the mid-nineteenth century, which presented at “nonsectarian,” but introduced the practices of bible reading and prayer, was really about indoctrinating children into Americanism, which meant Protestantism, republicanism, and capitalism. It qualified as a form of establishment: compulsory attendance, compelled contributions, governmental control of messaging, and suppression of alternatives.

Therefore, it was both invalid and coercive, and so too are the practices that came with it, namely, bible reading and prayer. Coercion is, apparently, not merely found in threat of loss of property or life, but anything that would facilitate the soft power of social stigma. The government, per the Establishment Clause, cannot even do that. It must, apparently, be completely neutral about what kind of practices and beliefs are socially encouraged or discouraged. Equal protection of life and limb by the law is not enough. Every child at every school must feel the same.

McConnell’s only frustration with Engel and Schempp is that coercion did not factor into the Court’s decision more. “Sect preference” as an element of establishment must be combatted at every turn, but so too must any of this social compulsion. Key for McConnell in Engel and Schempp is that the children are captive audiences. School is mandatory and the government dictates the curriculum. Hence, coercion within the environment. The only way to assess, for example, the constitutionality of a football coach to lead voluntary team prayer is to determine the “danger of coercion.” The Court’s decision in Kennedy “did not greenlight acts that have coercive effect,” and left the school prayer case intact. The test should be whether there is “proof of coercive effect” in the religious actions of authority figures.

But when discussing Espinoza, the authors conclude that the families seeking to avail themselves of a subsidy program for religious private schools were burdened but not coerced. Could it not be argued that the families were being pressured to send their children to secular private schools instead? That the government exhibited preference for a particular way of educating, a particular curriculum, a particular posture toward religion? Is this not social pressure? The children in Engel and Schempp, of course, were not barred from attending private sectarian schools instead of the public schools. They were not actually captive, after all. Both scenarios feature governmentally sponsored activity. But only one features coercion and the other does not. Why?

When President Washington prayed at his inauguration, they say, this was not coercive because no one was required to attend and no one was pressured to conform. Surely, though, the president, the highest office in the nation, is able to exert far more social pressure than any schoolboy. What is the rest of the country to think or feel when the commander in chief offers “fervent supplications” to “that Almighty Being who rules over the Universe” and “tender homage to the Great Author of every public and private good”?

Of course, Chapman and McConnell are right that such prayers, including ones offered in Congress, were not seen as establishment at the time, but what difference does that make? We’ve already established (pun intended) that the eighteenth century vision for religion in America has been superseded. The wild swinging between appeals to early American practice and understanding and modern shifts is all too convenient throughout the book. No one thought public religious symbols were an element of establishment at the founding, but can not these educate and coerce as much as public school prayer? Do they not make minority religions feel disfavored? Is there really any such thing as a “passive symbol” as the authors claim? Surely all are vectors of social pressure in some sense.

Chapman and McConnell are pleased that the Court has more recently relied on the idea of coercion more thoroughly, coercion being “the only principled way to explain the pattern of cases about public prayer.” Prayers at public school events are “in a fair and real sense obligatory,” but prayers at city council meetings are not. The difference being that no one is required to attend the latter. Since when are football games and graduation ceremonies mandatory? Does not the scope of a legislative session—the whole public—exceed that of a public school event?

Principled Pluralism?

Given how intricate to Agreeing to Disagree the principle of pluralism, of non-establishment, is, we should interrogate its pedigree. We have already seen that Chapman and McConnell depart markedly and swiftly from the original meaning and intent of the Establishment Clause. But perhaps the political principle that government should not regulate belief, virtue, religion, or culture is more historically stable. Perhaps the political morality of the founders will vindicate departure from their constitutional structure and interpretation. After all, constitutions are practical, consensus documents. The real constitution lies beneath and cannot always be fully expressed in formal documents. The question, in other words, is whether the political science of the founding justifies Chapman and McConnell even if their legal science does not.

To briefly recount the position of the authors: “The Establishment Clause is agnostic about religion. It favors neither the secular nor the religious, but instead reflects the idea that the nation’s public life should reflect the type and degree of religiosity of the people themselves, a religiosity shaped as little as possible by government.” Hence, “the Establishment Clause has facilitated the development of the most religiously heterogenous society the world has ever known,” and, by extension “value pluralism.” Indeed, the Establishment Clause’s alleged “requirement of religious neutrality” is what protects “cultural pluralism.”

Religious, value, and cultural pluralism—heterogeneity—that’s what the Establishment Clause “properly understood” is all about. Indeed, the whole First Amendment is about and for pluralism and diversity. For example, the authors gladly report that courts have generally upheld religious accommodations because this is a “good thing for religious freedom and diversity.” The “Religion Clauses work together to prohibit the government from using sticks or carrots to induce uniformity of religious belief and practice.”

Government

The question(s): Is the government in the business of shaping and regulating the morals and religion of its subjects? Does government have religious competency and cognizance?

As we’ve seen, the authors of Agreeing to Disagree answer both questions in the negative and think that this answer, this principle of political morality, is found in the Establishment Clause. That is, the principle of radical disestablishment, the principle found by the Everson Court as well in 1947. Remember, Chapman and McConnell think that the Court has gotten the Establishment Clause basically correct even if it has too often availed itself of incorrect vehicles and imprecise tests (e.g., Lemon).

We must spend significant time on this question because it is, at bottom, what Agreeing to Disagree is all about; parsing Establishment Clause precedent is merely the occasion for a bigger argument.

Would the founding generation have recognized this posture toward government, which we will define as the lawmaking authority, and morality? Would they have thought that government should leave morals and religion unattended and to the whim of the populace? Was government conceived of as agnostic to the types of opinions, beliefs, and practices the people held? Was government supposed to encourage and foster heterogeneity and pluralism? Beyond the founders, would people of the early republic have entertained any of this? If not, then it is hard to argue, as Chapman and McConnell do, that principles of agnosticism and pluralism are imbedded in the Establishment Clause.

In a passage less famous but congruous with his remarks to the Massachusetts militia, John Adams, writing to Mercy Warren, explained,

“The Form of Government, which you admire [i.e., monarchy], when its Principles are pure, is admirable indeed. It is productive of every Thing, which is great and excellent among Men. But its Principles are as easily destroyed, as human Nature is corrupted. Such a Government is only to be supported by pure Religion, or Austere Morals. Public Virtue cannot exist in a Nation without private, and public Virtue is the only Foundation of Republics. There must be a positive Passion for the public good, the public Interest, Honor, Power, and Glory, established in the Minds of the People, or there can be no Republican Government, nor any real Liberty. And this public Passion must be Superior to all private Passions.”

Going on, he reasoned that the form of government adopted does give “decisive color to the manners of the people.” Under a “well regulated commonwealth,” people are forced to be wise and virtuous out of necessity. If they do not, their chosen form will fail. Under a monarchy, people can be foolish yet the government endures. But there was a problem.

“But Madam there is one Difficulty, which I know not how to get over. Virtue and Simplicity of Manners, are indispensably necessary in a Republic, among all orders and Degrees of Men. But there is So much Rascallity [sic], so much Venality and Corruption, so much Avarice and Ambition, such a Rage for Profit and Commerce among all Ranks and Degrees of Men even in America, that I sometimes doubt whether there is public Virtue enough to support a Republic.”

That the people might lack sufficient virtue was not the real problem, however. The real problem was that the republic might lack men capable of leading the people to virtue.

“However, it is the Part of a great Politician to make the Character of his People; to extinguish among them, the Follies and Vices that he sees, and to create in them the Virtues and Abilities which he sees wanting. I wish I was sure that America has one such Politician, but I fear she has not.”

In some sense, then, Adams thought that government was not supposed to be agnostic toward the moral condition of the people. To be disinterested in the relative virtue of the populace would be to be unconcerned with the happiness of the same. It was, maintained Adams, the whole job of government to promote the general happiness of the people. Happiness and virtue were not neutral, empty terms for Adams or any of his contemporaries, just as the common or public good (being the aim and end of government) depended on some stable conception of the good.

Moreover, if a republic is the form best suited to the happiness of people but, in turn, requires virtue (i.e., happiness) of the people in order for it to endure, then a republican government is doubly interested in the moral state of citizens, both for their own sake and for the sake of the republic itself. Concern for maintenance of virtue is heightened in a popular state wherein the people have a share in lawmaking itself. This is why Benjamin Rush was so concerned about the education of youths, and specifically prescribed education in the religion of the New Testament.

“Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports… And let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.”

Washington was not agnostic or neutral on this. But it was not just happiness but security that necessitated concern with virtue. Writing to James Warren, Adams explained,

“It is our Business to render our Country an Asylum, worthy to receive all who may wish to fly to it. This can only be done, by rendering the Minds of the People really independent—By guarding them against the Introduction of Luxury & Effeminacy—By watching over the Education of Youth—By keeping out Vices and cultivating Virtues—By improving our Militia, and by forming a Navy. These alone can Compose a Rock of Defense.”

Important to remember also is that America in the eighteenth century was not an individualist but a communalist society, as both Barry Shain and Donald Lutz have demonstrated. Shain convincingly argues that standards of virtue and morality were developed and applied by communities, not individuals, as standards of civil participation which were then reflected not merely through the soft power of stigma but through legislation. Protestantism was the guiding light of these communal standards of virtue and piety. Chapman and McConnell would have found the type of social stigma applied by authority figures to be highly coercive. Speaking of education, again, Lutz reports that American writers frequently “noted a connection between morals and prudence: religion and religious education were the primary means of inculcating the desire to pursue the common good.” And this was a communal, state interest. Alluded to already is that in a republic, under a theory of popular control, “The people in a community have a common interest in protecting and preserving their shared values, interests, and rights.” That’s what a community, a society, a nation is, and its longevity is not a matter for passive consideration or neglect, nor is it an amoral (agnostic) thing.

Moving from theory, we can readily observe a fact, namely, that morality and religion were heavily regulated (from our perspective) in the early republic. If a principle of agnostic pluralism was imbedded in the First Amendment, Americans violated it immediately and constantly. If a political principle of radical non-establishment was secretly inserted into the Establishment Clause, Americans were entirely unaware of it. William Novak has chronicled how regulated health, safety, and morals were throughout the nineteenth century. Even after formal disestablishment, blasphemy, Sabbath, and obscenity laws were enforced up into the twentieth century.[1]

More than that, expectations that government retained concern for morality and religion was the actual principle imbedded in the minds of those at the founding. As James Hutson has pointed out, Americans of the founding generation still expected government to be a nursing father to religion. Indeed, the metaphor from Isaiah “expressed the view of the Founding generation toward the relations between government and religion far more accurately than Jefferson’s wall metaphor.”

Elisha Williams preached in 1744 that “civil authority are obliged to take care for the support of religion, or in other words, of schools and the gospel ministry, in order to their approving themselves nursing fathers.” Williams assumed that this was a proposition that “everybody will own.” Edward Dorr, preached similarly, as did countless other ministers up through the eighteenth century. It was assumed that religion was necessary to the happiness and stability of society and that its prevalence, therefore, constituted a state interest.

State legislatures affirmed the same. The Maryland House of Delegates, for example, declared in 1785 that maintenance of Christianity was intricate to national endurance.

“We cannot conclude this address without recommending to your serious attention the observance of the Christian religion, in its genuine purity and simplicity. We conceive it to be the indispensable duty of every legislator to encourage, by precept and example, the practice of those moral virtues which are the brightest ornaments of human nature, and the surest support of civil society. The decline of religion and morality is the never-failing forerunner of national ruin; and we trust that a people who have so gloriously asserted and maintained their liberties will never suffer the sacred fire of genuine piety to be extinguished on their altars.”

Every founding father, from Washington to Adams to Hamilton, repeated the maxim that religion was necessary for virtue and virtue was necessary for a republic. If the type of regime given to the American people required a virtuous citizenry, then it required religion. To be agnostic toward the moral and religious condition of the people was to be suicidal. It is true, as Hutson further indicates, that the reduction of religion to “public utility” degraded its importance “to the level of other activities” that concerned the state. An attitude which, in turn, contributed to disestablishment by the mid-nineteenth century.

The Christian scope obviously controlled any notion of broadening toleration. If Washington and John Jay were right, then Americans enjoyed high homogeneity which, in turn, facilitated a degree of liberality. They were agreed on their “religion, manners, habits, and political principles.”

Given the assumptions above, had the power of police, to regulate morals and religion, not been invested in the states, had there been no level of government charged with this domestic regulation, the Americans of the founding generation would have considered the whole thing illegitimate, as lacking an essential function of government.[2]

The Amendment

Beyond the political assumptions of Americans in the founding and early republic eras, we can also find a refutation of Chapman and McConnell in the purpose and scope of the First Amendment in commentators more proximate to drafting and ratification of the same.

Aforementioned is that Jefferson evidently interpreted the Establishment Clause as a strict jurisdictional provision. His opinion was expressed both publicly and privately. Since space does not permit exhaustion of source material on this point we will turn to the best, namely, Joseph Story, Madison’s nomination to the Supreme Court.

For Story’s part, he was convinced that “government cannot long exist without an alliance with religion to some extent.” Christianity was the best friend of “free governments.” Story, writing to Jaspar Adams, was clear that a distinction was to be made between general and particular establishment. He did not desire the establishment of a particular sect of Christianity, only the general “Establishment of Christianity itself.” That is, the general Christianity spoken of in Updegraph v. Commonwealth and Vidal v. Girard’s Executors as imbedded in the common law.

More to the point, Story begins his coverage of the Establishment Clause by affirming

“the right of a society or government to interfere in matters of religion will hardly be contested by any persons who believe that piety, religion, and morality are intimately connected with the wellbeing of the state, and indispensable to the administration of civil justice.”

The essential doctrines of general Christianity he has in mind, and that the state has an interest in maintaining are the existence of God, the accountability of man to God, a future state of rewards and punishment, and the cultivation of virtues— “these never can be a matter of indifference in any well-ordered community.” Story adds that it is “difficult to conceive how any civilized society can well exist without them.” Further, especially in a Christian society like America of his day, it is impossible to “doubt that it is the especial duty of government to foster and encourage [religion] among all the citizens and subjects.” This conviction did not negate a right of private judgment or freedom of worship. The point is simply that government, at least rational government, cannot neglect the cultivation of religion.

The only difficulty is determining the proper means and limits of achieving this end. The question is not whether religion—for Story, Christianity—should be promoted but how. Story outlines various modes of establishment. The first presented is the one, per his letter to Adams, he favors wherein the Christian religion is established without preference for any particular sect.

Like Justice David Brewer, Story concludes that America is a Christian nation, looking back to its first charters and state constitutions, and that “few persons” would “contend that it was unreasonable or unjust to foster and encourage the Christian religion.” It was simply a matter of sound policy. Indeed, Story surmises that at the time of adoption of the First Amendment “the general if not the universal sentiment in America was, that Christianity ought to receive encouragement from the state” so long as rights of conscience and worship were protected. “An attempt to level all religions, and to make it a matter of state policy to hold all in utter indifference, would have created universal disapprobation, if not universal indignation.”

Accordingly,

“The real object of the amendment was not to countenance, much less to advance, Mahometanism, or Judaism, or infidelity, by prostrating Christianity; but to exclude all rivalry among Christian sects, and to prevent any national ecclesiastical establishment which should give to a hierarchy the exclusive patronage of the national government.”

All sects, even including infidels, would not be precluded from “the common table of national councils.” (Of course, the states were an entirely different story.) In this way, the Establishment Clause was very much like the religious policy of expanded toleration in Cromwellian England. As Blair Worden has shown, Christian unity was the impetus for extending freedom of public exercise to Presbyterians, Congregationalists, and Baptists in the Protectorate.

Story’s explanation is clear. The Establishment Clause was a jurisdictional provision. Far from introducing a principle of indifference, agnosticism, or neutrality, it was a practical mechanism. The assumptions behind this mechanism were that America was a thoroughly Christian nation and that people expected Christianity to be privileged and even government (at some level) to be active in fostering its prevalence without allowing denominational differences, which corresponded to regional and state differences, to interfere with or overtake the new national (federal) government. Nowhere does Story suggest that a more comprehensive allegiance to pluralism or non-establishment was in play. Courts affirmed this reading. In Muzzy v. Wilkins (N.H. 1803), Chief Justice Jeremiah Smith explained that

“The Constitution, viewing religion in some form or other as useful if not indispensably necessary to make good subjects; not being able to decide between contending sects as to which is most agreeable to the Word of God, the infallible standard, but viewing them all as equally good for the purposes of civil society, because they all inculcate the principles of benevolence, philanthropy, and the moral virtues; considering too, that public instruction in the general principles of religion and morality can only be maintained by enabling corporate bodies to support and maintain it—under these impressions and with these views, confers the powers in question.”

Mad Madison

Albeit early on Chapman and McConnell acknowledge that founding fathers other than James Madison are relevant to the conversation, they cite Madison more than anyone else. More than that, their approach to religion is entirely Madisonian. The authors, indeed many scholars, might even appreciate and embrace this characterization. Yet, the Madisonian vision is problematic if for no other reason than that it is not representative of the founding generation and, therefore, tells us little about the meaning, purpose, or intent behind the First Amendment. As Madison himself, radical as he was, would have insisted, it is not the intent of the drafters of a provision that is informative but the intent of the ratifiers who adopt said provision that controls. It does not matter what Madison wanted. What matters is what the state legislatures thought they were getting.

That Madison, and his partner in crime (Jefferson), were the minority report on religion at the time has been demonstrated repeatedly. Madison’s own radicalism is less understood. His strict separationism and absolutist opposition to any government assistance of religion was shared by none of his contemporaries. Even Jefferson was less absolute in practice. That Madison would oppose a system of voluntary assistance of all churches in Virginia speaks to his radicalism. That he thought government should have no concern for the moral character of its citizens, and that he denied the benefit of religion to encouraging virtue were extreme positions that, admittedly, are hardly extreme anymore.

Plutarch had instructed that commonwealths could not survive without religion. Madison rejected the ancient advice for David Hume’s skepticism, though even Hume believed that some religious establishment was probably required for the stability and comfort of the vulgar. James Hutson concludes that Madison’s “pessimism about the social value of religion” was so extreme that he was separated from all other founders, “Jefferson included.” “Arguably, [Madison’s views] separate him from any Anglo-American statesman before John Stuart Mill.” Madison denounced the tradition of congressional and military chaplains and complained about religious corporations like “sectarian seminaries,” which he thought should be stripped of their charters by state governments. “The sacred principle of separation of church and state,” observes Hutson, “could, apparently, be comprised, if the wrong kind of religion or a rich kind of religion was being protected by objectionable legal vehicles.”

Madison’s approach was “market-oriented,” in the extreme, like market fundamentalism of laissez-faire economists. And Hutson surmised that Madison was not so much propelled by a belief that a free market would benefit religion. The Great Awakenings, after all, started in areas with long histories of religious establishment, and “Madison himself explicitly denied that separating church and state had created a bull market in religion.” Rather, Madison likely thought his view, if fully enacted, would diminish the potency of religion. It was Hume who saw that religion decays under toleration and that state indifference to religion encourages the same attitude in citizens. No other founder expressed desire for this outcome nor intentionally facilitated its fruition.

Observing that Madison’s views about church-state issues and religion generally were “radically idiosyncratic” and singular, James Hutson once asked why Madison has such a “substantial following on the ‘religion question’ in our own day?”

“The answer is simple. For a variety of reasons many present-day Americans agree with the separationists results he sought and, like their fellow citizens at all points on the ideological compass, believe that sailing under the flag of a distinguished Founding Father is a good way to reach their political destination.”

Agreeing to Disagree is no exception to this rule. Though we must acknowledge that Chapman and McConnell are on the right side of history. Madison won. Government’s increasing indifference to religion over the past century has tracked with the steady decline of Christianity and the rise of aberrant faiths. Even the heterodox founders would have been appalled by what passes for virtue and piety today and how thoroughly religion has been relegated to private life. Perhaps, Chapman and McConnell should consider that this result is a cause rather than a product of current political instability and division. Maybe cultural and religious heterogeneity is not quite the blessing of liberty they think it is. Can members of any coherent, peaceable polity really agree to disagree on fundamental moral and religious questions that determine their shared way of life? Can they share a way of life wherein these things are unsettled?

Justice Potter Stuart foresaw that the new Establishment Clause jurisprudence, post incorporation, would not inaugurate some nirvana of neutrality, but a national, uniform secularism, a hostility to Christianity, to be specific. What Chapman and McConnell do not wrestle with, but must, is the result of what they defend. What evidence is there, ancient or modern, that a truly neutral, amoral regime is possible? Like all liberals (right of left), perfection, political paradise, is just beyond the horizon and delayed only by the stubborn anachronisms of human nature and political realities.

Conclusion

Chapman and McConnell may have their complaints about contemporary Establishment Clause interpretations, but their vision for future correctives is not less but more, broader, and more thorough disestablishment. For them, the long process of disestablishment remains to be completed. That it has come, in part, through means explicitly precluded by the Clause itself or unimaginable and unintended by earlier generations of Americans is no matter. The principle they discover within the Clause supplies a new political morality.

Their concern is division, not the basis of division. Their goal is plurality, diversity, and heterogeneity. It does not bother them that no political thinker of the eighteenth century would have held these up as workable, much less laudable, goals. The reader is supposed to believe that the brilliance of a provision which maintained state-level established religions and precluded federally imposed uniformity introduced a political principle of governmental indifference to virtue and vice, religion and culture, and bid American descendants to pursue heterogeneity for its own sake. Chapman and McConnell provide no limitations on this pursuit.

Again, their concern is tempering of divisions; no positive moral vision is offered, no moral and religious boundaries. Chapman and McConnell offer a suicidal regime, one that is agnostic on whether the republic is secular or religious, and indifferent to what kind of religion. Apparently, the framers of the First Amendment threw off the instructions of the Romans they otherwise studiously mimicked—Polybius being the favorite historian—and charted a new course wherein religion, which provided the success of Rome, was no longer a concern, the state had no interest.

But that’s not quite right. What Chapman and McConnell present is a new religious dogma, principled pluralism, the values and dictates of which can openly be taught in schools, its preachers compensated by public funds, and so on. It claims to be neutral and, therefore, free from the restrictions applied to all other religions. The religious establishment that Chapman and McConnell endorse is the current one, that of post-war liberalism. The strong gods—those strong loves of faith, family, and flag—are put out to pasture where they can no longer cause mischief. In their place are the dogmas of tolerance, neutrality, diversity. All other beliefs are privatized, precluded from endorsement by public, political power. The point of government, on this view, is to ensure that no one ever wins, that no view is ever predominant. Well, no view except the view that no view should be predominant. This view must be religiously enforced.

Chapman and McConnell want it both ways. Religiosity should be “shaped as little as possible by the government.” Yet, “the nation’s public life should reflect the type and degree of religiosity of the people themselves.” And yet again, the authors deny the right of popular control, that is, for people to express and protect their religiosity through legislative power. In this sense, Chapman and McConnell deny the very basis of republic government, of majority rule, of nationhood itself… at least as the founders understood it.

[1] See generally Timon Cline, “Well-Regulated for Well-Being: Public Health and the Public Good in 19th and Early 20th Century American Caselaw,” 16 U. St. Thomas J. L. & Pub. Pol’y 147 (2023); “Blasphemy and the Original meaning of the First Amendment,” 135 Harv. L. Rev. 689 (2021).

[2] See Lutz, The Origins of American Constitutionalism (Louisiana State University Press, 1988), 96 (“… the Constitution is an incomplete foundation document until and unless the state constitutions are also read”). See generally Max Edling, Perfecting the Union: National and State Authority in the US Constitution (Oxford University Press, 2020).