A Model Jurist in Alabama

It is disheartening that our society is so saturated with closed minded people. I mean this literally, not colloquially. Intellectually, our operative mental frame is, evidently, narrow in the severe—formulaic and, worst of all, boring. Our jurists are not immune from this. Most sequester themselves from anything outside the words on the page, bare procedure and “precedent.” When they do dare to venture into history and tradition it is usually meager, approved versions of each. In other words, our modern jurists—judges and scholars alike—do not conceive of the object of their rulings, viz., man… sociable man. To consider such things would demand awareness of things existing beyond the strictures of positivism like metaphysics and revelation.

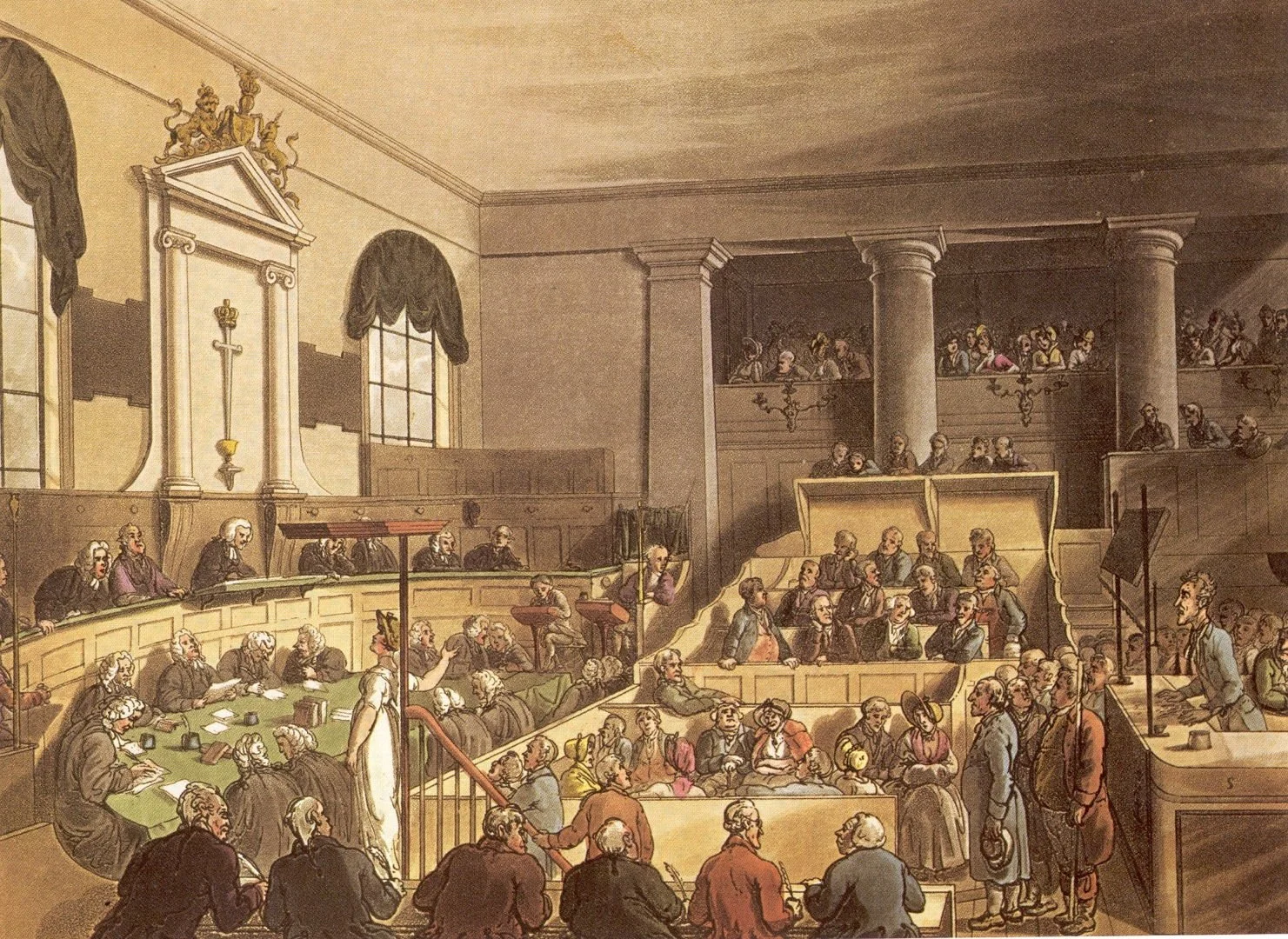

But, as I have written before, there was a not-so-distant time when such data was not only readily available to the jurist but an intricate part of his discipline. It was expected that he would possess knowledge of the origins, ends, and nature of man, society, and government. The law lectures of James Wilson and Chancellor Kent attest to this. Moral-theological foundations must be laid before any jurist can proceed on to adjudicating concrete human affairs. For this he must often look outside his own discipline, or rather, expand his horizons—they used to study more than caselaw at the Inns of Court.

Moreover, whilst our contemporary cultish obsession with feigned neutrality seeks to cast out morality and religion—the higher law—Anglo-American law used to not only recognize such things but actively and forthrightly incorporate them. Joseph Story, David Brewer, and many others affirmed time and again that Christianity was ingrained in the common law, supplying it with both moral and intellectual mooring; and it reflected the convictions and commitments of the particular people for which it adjudicated conflict, secured privileges, and safeguarded tranquility. Stuart Banner has done the best work on this common law feature. Steven Green has provided expert study in the use of the Decalogue in this regard.

Given that most of this practice and tradition is being actively eroded it is refreshing, to put it inadequately, when a judge slip free from the surly bonds of earth and appeal to heaven, as it were. That is, when a judge brings the full weight of revelation and human knowledge to bear on the case in controversy thereby elevating himself beyond glorified statute parser: a fully integrated mind.

Enter the Alabama Supreme Court. Just last week, to the shock of nearly all observers, the court ruled in LePage v. Center for Reproductive Medicine, P.C., that frozen embryos are, in fact, human children (“extrauterine children”). Quite right. What else could they be?

The question was whether a fertility clinic that was negligent in securing its facilities could be sued by the parents of dead embryonic children. The court said, yes. As a result, something like half of the state’s in vitro fertilization (IVF) clinics were forced to shut down out of fear of prosecution under Alabama’s Wrongful Death of a Minor act.

This is a truly monumental development of the kind that many pro-life Christians have been hoping for, for years. (For an explainer on the positions of various denominations on IVF, see this excellent two-part series from Emma Waters here and here.)

That said, the majority opinion and primary holding is of less interest here, for our purposes, than the special concurrence by Chief Justice Tom Parker (beginning on page 26). A good, brief explainer of the decision is available here. The key line from the Parker concurrence cited by most commentary is that the Alabama constitution, per a 2018 amendment, “declares and affirms that it is the public policy of this state to recognize and support the sanctity of unborn life and the rights unborn children, including the right to life.” This alone is enough to garner Chief Justice Parker acclaim. But, again, there is more to his method than the conclusion. How did he get there?

His stated mission at the outset is to define “sanctity of unborn life,” since it appears in the provisions applied by the majority to the question at hand. The state constitution itself does not define the term. Parker exhibits an originalist-textualist bent, but, as we shall see, of an expansionist variety. Its not all dictionaries and the Federalist Papers for Chief Justice Parker. He draws from “deeper wells,” offering a master class in how judges today can expand their analysis to reach into these wells.

“(1) the history of the period, (2) similar provisions in predecessor constitutions, (3) the records of the constitutional convention, inasmuch as they shed light on what the public thought, (4) the common law, (5) cases, (6) legal treatises, (7) evidence of contemporaneous general public understanding, especially as found in other state constitutions and court decisions interpreting them, (8) contemporaneous lay-audience advocacy for (or against) its adoption, and (9) any other evidence of original public meaning, which could include corpus linguistics.”

At the time of the adoption of the provision in question, “sanctity” meant “Godliness” and “inviolability.” Despite the protestations of those who would secularize its meaning, Parker embraces its fullness, noting that the Alabama Constitution itself invokes “Almighty God” and the endowment of human life from God. Standard fare common law concepts, the common law being expressly incorporated into Alabama state law.

Now, the door has been opened to Blackstone’s declaration of God’s grant of human life, the “image of God” as articulated in the Manhattan Declaration—offering an example of continued and contemporary usage—along with caselaw are brought in. In a way, at this juncture, Parker has established Christianity’s relevance for state law given the incorporation of its theological lexicon into the same.

Hence, Peter Van Mastricht—specifically the edition of Theoretical-Practical Theology edited by Joel Beeke and Todd Rester—is quoted at length for the connection between the common law recognition of the image of God and the rule that it cannot be intentionally taken without justification. (A nice biographical footnote on Van Mastricht is included.) Van Mastricht’s continuity with Augustine and Thomas Aquinas is mentioned also. Calvin’s commentary on Genesis and the Institutes are afforded lengthy quotation as well.

Chief Justice Parker brings it home by concluding that if “sanctity of life” provides the guiding policy rationale and the state constitution invokes God for authority, then, based on the included theological commentary, the unjustified taking of human life is an affront to God himself contra the constitution. The concurrence goes on to consider more relevant caselaw and the like, but the section just highlighted is distinct insofar as it bothers to lay the moral basis within the western Anglo-American common law (and Christian) tradition for a constitutional provision rather than settling for a bare textual hook. Read the whole thing for yourself.

The Chief Justice’s concurrence is the most inspiring and creative legal writing I’ve seen since District Court Judge Justin Walker’s Covid era memorandum providing Kentucky churches with exemptions on Easter, or Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk’s ruling blocking FDA approval of abortifacients, in which he insisted on referring to babies in the womb as “unborn humans.” I hope we see more from Chief Justice Parker and that others emulate him.