There Are No Originalists Now

Connecticut received its charter from Charles II in 1662. Prior to the return of Stuart government, Connecticut had never been officially recognized as an independent colony by the English government though it considered itself to have existed since the Fundamental Orders had been adopted in 1639. The charter granted certain prerogatives of self-government under English oversight.

In 1686, colonies from Jersey to northern Massachusetts (Maine) were consolidated at the directive of James II under the rule of royal governor, Edmund Andros. Singular rule of half the eastern seaboard, and by a foreigner. It was an unprecedented move, especially from the perspective of New Englanders notoriously tenacious of their liberties. Andros demanded the surrender of all colonial charters—now considered obsolete. The Massachusetts Bay charter, significantly older than that of her sister colony, had already been revoked in 1683.

Royal appointees would thenceforth serve as governors. For a time, the legislature was dissolved, as it would be again a century later. Town meetings, the bedrock of New England politics, which even Thomas Jefferson admired, were restricted. Laws passed by local legislators were abolished or revised. The Andros regime was a total overhaul. In an obvious affront to the Puritans, Andros held Episcopal services in Boston churches. Perhaps most frustrating were increase in duties on goods, especially alcohol, a fact that confuses contemporary assumptions about Puritan New England.

Connecticut ignored the request to relinquish its charter, operating as if nothing had changed. Naturally, Andros himself (and an armed escort) ventured to Hartford to retrieve it. At the meeting with the governor and leaders of the colony, the charter was laid out on a table before the parties. The debate was not going in the colonist’s favor. According to legend, the candles were suddenly blown out and one Joseph Wadsworth snatched the parchment from the table and fled, hiding it in a white oak tree on a nearby estate.

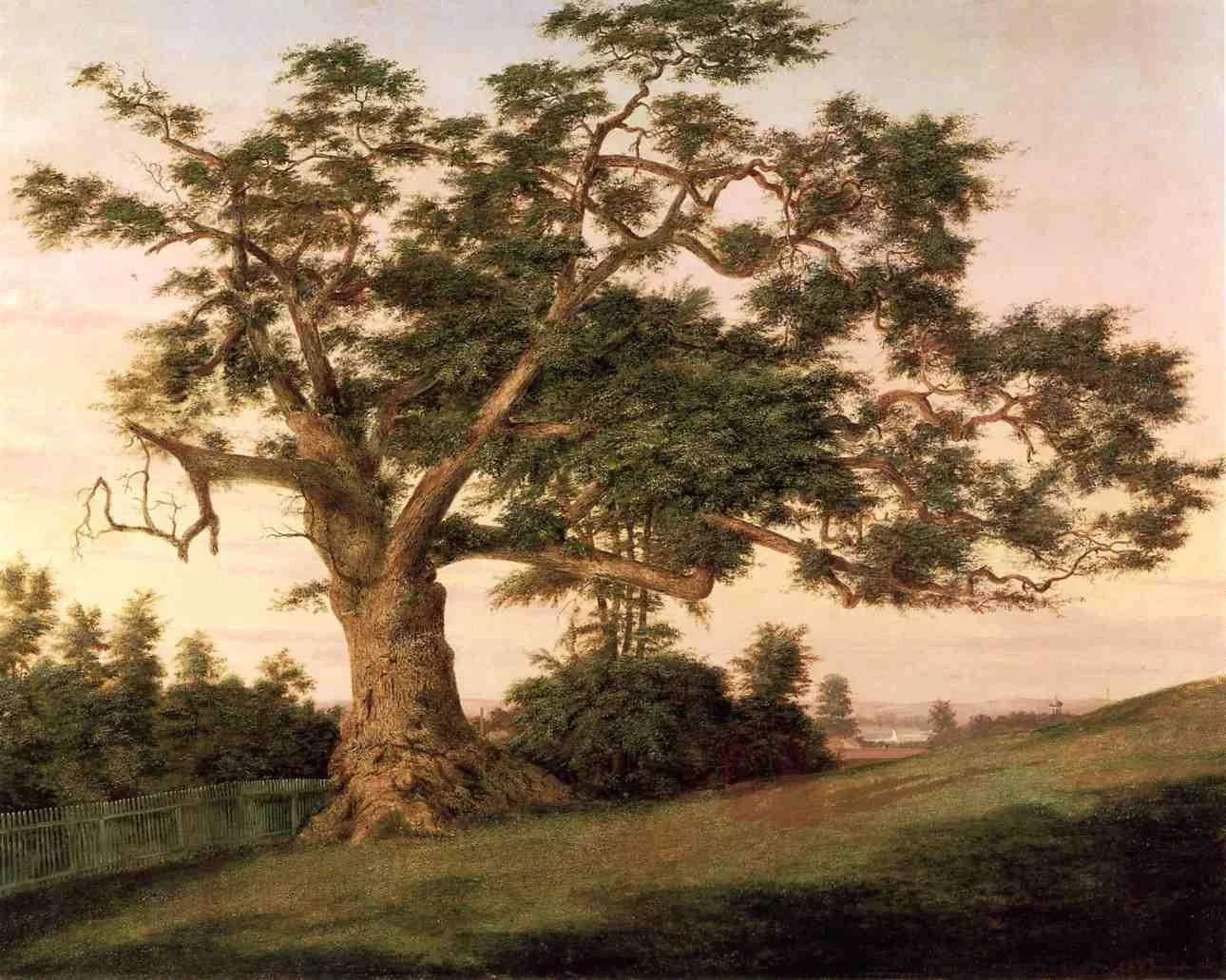

Thus, the legend of the Charter Oak was born. The tree itself, supposedly centuries old, stood until it fell in a storm in 1856. Even after its demise, it remained a symbol, like the New England pine, of American independence, appearing on Connecticut’s commemorative quarter in 1999.

Wadsworth’s stunt did not prevent the Andros regime from assuming its power. Even the first American “tax revolt” in 1687 did not alter the situation. It was only the regime change of 1688 that freed the colonists from what was called the Dominion of New England. This whole episode, the American side of the late seventeenth century revolution, still very much framed the imagination of colonists a century later, as the Novanglus and Massachusettensis exchange suggests. What is curious and humorous is that the Connecticut colonists thought the act of securing the physical copy of their charter would matter at all. Andros was annoyed but not deterred, obviously.

Constitutional originalists are like those noble Connecticut colonists. Their spunk is to be admired, to be sure. But their understanding of things is entirely parochial. Hiding the charter in a tree does not change the fact of rule; it does not dictate the constitutional order. Whether you like it or not, you are captive to it.

The morning after Wadsworth squirreled away the charter, Connecticut surrendered itself to Andros who then proceeded to dissolve the legislature and make new judicial appointments. Even as the 1662 charter sat securely in a hardy oak, Andros ruled. Query whether when the charter is recovered from hiding it is understood as it was before. As the colonies found out, the new regime of William and Mary did not entail a true return to prior liberties. 1639 was very different than 1689.

Not only did the structure and balance of power between king and parliament radically shift, but the undergirding constitutional morality also changed. Locke’s Two Treatises of 1689 differ from his Two Tracts of nearly thirty years prior—and both differ from the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina— but neither would have been well received by the earlier Stuarts. Had Locke and Robert Filmer written in the 1630s rather than the 1680s, there is no question who would have gotten the better of the contest. Richard Baxter, who fancied himself a moderate episcopalian and monarchist, found out the hard way in 1659 that even the suggestion of balance or mutual dependence between king and parliament was unwelcome. By the turn of the century, the basis for legitimacy and the origin of government itself had shifted markedly from divine dictate to consensual contract.

According to some accounts, Wadsworth held on to the Connecticut charter until 1715, the last year, as it happens, that an English monarch ever exercised the veto power. That is, the last time that the constitution of 1689 ever behaved according to its original, formal structure. Even then Queen Anne was not Charles II. Same title, very different job. The constitution had changed and then changed again. The position and status of the colonies within the English constitution changed with it. On (metaphoric) paper, however, it would have appeared that little had changed.

The real problem with originalists is that there are no originalists. Jesse Merriam did not say this in his recent salvo at The American Mind. He did not mention originalists or originalism at all, in fact. He keeps it above the board. I will continue no such politeness.

What Merriam expertly charts in his essay demonstrates the point. Most insightful is Merriam’s account of the eras of constitutional morality. There have been at least four over the past 150 years, from Lochner to the New Deal to Civil Rights. If we stretch back further, Reconstruction would represent another era.

At each stage, the meaning of the constitution conforms to the predominate, animating constitutional morality, or more pointedly, the political regime. The operative morality is what directs and constrains interpreters of the constitution, judges, executives, and legislators alike.

As Merriam explains, we are currently in the Civil Rights era which is “structured around two propositions: (1) diversity is our greatest constitutional good, and (2) discrimination is our greatest constitutional evil.” This morality governs both political and legal considerations, it is the true constitution, the fundamental law, the spirit that gives the formal constitution life. The unwritten constitution is the soul to the body. As Joseph de Maistre famously quipped, “That which is written is nothing.” (Nota bene Justice Gorsuch said the exact opposite in Bostock v. Clayton County.)

There are no originalists because no one shares the constitutional morality of the founding. Originalists, like any other guild of interpreters, are always captive to the prevailing constitutional morality of their time which is, the Civil Rights morality. That diversity, as opposed to homogeneity, strengthens democracy, and that discrimination is a grave ill still pervade originalist thought.

For all their appeals to the founders for support, originalists do not think as the founders did. Originalists are subjects of our contemporary regime, not the political morality of the founders. They may (selectively) invoke the words of the founders, but they often filter the meaning through present morality.

Take the subject of religion as illustrative here. The point of the illustration is not to make a substantive judgment but only to emphasize the distinction between two political moralities.

“[O]ur constitutional tradition, from the Declaration of Independence and the first inaugural address of Washington, quoted earlier, down to the present day, has, with a few aberrations, see Church of Holy Trinity v. United States, 143 U. S. 457 (1892), ruled out of order government sponsored endorsement of religion… where the endorsement is sectarian, in the sense of specifying details upon which men and women who believe in a benevolent, omnipotent Creator and Ruler of the world are known to differ (for example, the divinity of Christ).”

Scalia dissenting, Lee v. Weisman (1992). The “aberration” Scalia refers to is the declaration of America as a Christian nation which, in the late Justice’s opinion, was rather sectarian.

To be sure, Scalia was right about the historic practice of public prayer and the like even at the national level being acceptable to, and no violation of, the Establishment Clause. This much is properly gleaned from history. And again, Scalia knew, of course, that the Clause was not originally incorporated. His purpose was to prove that on either side of incorporation, the majority was wrong about the practice in question and whether it represented “coercion,” a test he did not like. (As I’ve pointed out before, originalists like Michael McConnell did find school prayer “coercive.”)

But in Scalia’s dissent, we see an inclusive monotheism utterly foreign to the founding era.

Justice John Paul Stevens later threw Scalia’s Weisman (and McCreary County) dissent back in his face in Van Orden v. Perry (2005). Doubtless he was waiting for the opportunity. Motives aside, Stevens, the non-originalist, was right. Stevens understood, or was at least willing to admit, the political morality of the founding better than the originalists.

“Simply put, many of the Founders who are often cited as authoritative expositors of the Constitution’s original meaning understood the Establishment Clause to stand for a narrower proposition than the plurality, for whatever reason, is willing to accept. Namely, many of the Framers understood the word “religion” in the Establishment Clause to encompass only the various sects of Christianity.”

Stevens (rightly) cites Joseph Story to make the point that the scope of the founders was much narrower than that of the plurality in Van Orden. Per Story, the purpose of the First Amendment was

“[N]ot to countenance, much less to advance Mahometanism, or Judaism, or infidelity, by prostrating Christianity; but to exclude all rivalry among Christian sects, and to prevent any national ecclesiastical establishment, which should give to an hierarchy the exclusive patronage of the national government. It thus sought to cut off the means of religious persecution, (the vice and pest of former ages,) and the power of subverting the rights of conscience in matters of religion, which had been trampled upon almost from the days of the Apostles to the present age.”

Stevens, again:

“The original understanding of the type of “religion” that qualified for constitutional protection under the Establishment Clause likely did not include those followers of Judaism and Islam who are among the preferred “monotheistic” religions Justice Scalia has embraced in his McCreary County opinion… The inclusion of Jews and Muslims inside the category of constitutionally favored religions surely would have shocked Chief Justice Marshall and Justice Story. Indeed, Justice Scalia is unable to point to any persuasive historical evidence or entrenched traditions in support of his decision to give specially preferred constitutional status to all monotheistic religions… Justice Scalia’s inclusion of Judaism and Islam is a laudable act of religious tolerance, but it is one that is unmoored from the Constitution’s history and text… Given the original understanding of the men who championed our “Christian nation”—men who had no cause to view anti-Semitism or contempt for atheists as problems worthy of civic concern—one must ask whether Justice Scalia “has not had the courage (or the foolhardiness) to apply [his originalism] principle consistently [McCreary County].”

Then Stevens outlined (again, correctly) the real Establishment Clause test of the founders:

“Indeed, to constrict narrowly the reach of the Establishment Clause to the views of the Founders would lead to more than this unpalatable result; it would also leave us with an unincorporated constitutional provision—in other words, one that limits only the federal establishment of ‘a national religion.’”

In other words,

“Under this view, not only could a State constitutionally adorn all of its public spaces with crucifixes or passages from the New Testament, it would also have full authority to prescribe the teachings of Martin Luther or Joseph Smith as the official state religion. Only the Federal Government would be prohibited from taking sides, (and only then as between Christian sects).”

Unless originalists are ready to “cross back over the incorporation bridge,” then they should probably stop citing the founders for support. Much better, concluded Stevens, to simply own the broad principles, for which the founding might provide you with some sentimental inspiration, that remain relevant to you today and fit them into constitutional construction. Meaning, Stevens was demanding that the originalists make a choice between two dueling political moralities. Have we not construed the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to “prohibit segregated schools” in Brown v. Board of Education? The drafting records of the Amendment suggest no such intent, but what originalist is crusading to overturn Brown?

The operative political morality of the originalists in both cases above is still today’s political morality, not that of the late eighteenth century. It might be a slightly outdated version, but it is still the same software.

Regarding the First Amendment, principle of the founders was Christian unity; the principle of the originalists and non-originalists alike is some version of inclusivity (diversity) and non-coercion (antidiscrimination). It is just a question of line drawing. History is employed to glean varying results in cases and controversies but not diametrically opposed principles.

We do not find this inclusive monotheism in Connecticut. As one of two colonies ignored the call in 1776 to draft new constitutions, Connecticut’s 1662 charter served as its constitution until 1818. Among other archaic things, the charter commits the colony to converting “the Natives of the Country to the knowledge and obedience of the onely true God and Saviour of mankind and the Christian faith.” Indeed, this was the “onely and principall end of this Plantacion.”

It was a felony in Connecticut for any professing Christian to promulgate or practice atheism, polytheism, unitarianism, or to otherwise deny Christianity and the divine authority of the Bible. On the first offense, the criminal was precluded from holding civil office. For the second, the right to bring lawsuits or be a guardian of a child or executor of a will or estate was denied. All this on top of the common Sabbath, blasphemy, and obscenity laws, and religious tests for office, which pervaded the states throughout the nineteenth century. These are all expressions of the constitutional morality of the founding and early republic. Does any originalist endorse it, either the means or the end?

Rhode Island was the other colony to initially refuse the call for a new constitution in 1776. Its 1663 Charter certainly presented a liberty of conscience, but not one that could be described as inclusive monotheism. Rhode Island barred Roman Catholics from public office and Jews from citizenship until 1842 even as they relaxed certain laws in the late eighteenth century to accommodate the practices of the former before the new constitution was adopted. Rhode Island might have been uniquely tolerant of Protestant dissenters in its day, but even Roger Williams, faced with the realities of governance, narrowed his scope by the end of his life and that was because of sects like Quakerism—no Islam in sight.

The operative principle for Connecticut, Rhode Island, and the rest, when it came to religious liberty, was the same (at bottom) as it was in Cromwell’s England, viz., ecumenical Protestant unity. (The same principle can be found in William Penn.) Toleration was, of course, afforded to others. It was a synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, after all that Washington famous corresponded with.

Yet, there is no escaping the fact that colony and early state leadership was limited to Christians generally—who could affirm some very Protestant tests for office—and in many cases Protestants in particular, as in New Jersey, for example, or that the favored public teaching would be Protestant, as in Massachusetts. And this conclusion springs from constitutions and laws alone; if we accounted for the uncodified cultural stigma—everything was coded Protestant—the case would be stronger. In other words, there was a cultural center and presumption reflected in law that was far narrower in scope than originalists care to admit, and this scope conditions (or should) understanding of other provisions, like the First Amendment. To not think in the original terms and remit is to miss the original impetus, function, and meaning entirely.

As Glenn Moots has pointed out, no one cared much about Roger Williams until fairly recently. But if even Rogue Island did not reflect the inclusivity and antidiscrimination of originalist monotheism, where is it to be found? More pressingly, where is a true originalism to be found, one not subject to the present constitutional order? Originalists may successfully combat some innovations, but they are incapable of overriding the underlying, governing propositions. Originalists may not think that diversity is our greatest strength, or discrimination our greatest evil, but they still find the principles inescapable.

Wittingly or unwittingly, they operate within the same frame, and this corrupts their own method. This fact demonstrated by their unwillingness to assert the political morality of the founding as it was. You can hide the charter in a tree for a century, but this does not stop regime change, and when you finally pull it back out, if you can still read it, it may not make much sense to you anymore.